Gymnazium na Zatlance (secondary school) - Czech Republic

Region: Prague

The other schools in the Quad Blog: Escola de A Ver-o-Mar (Portugal), Institut Vicenc Plantada (Spain), Oulun Suomalaisen Yhteiskoulun Lukio (Finland)

Creative Connections Project: Personal Stories/ identity/comics

Background: A profile of the school and participants

This case study describes the action research which took place at the high school Gymnazium na Zatlance and the pilot study at the gallery Trafacka. The team consisted of several specialists: the art teacher, researcher and comic art educator, some MA students observing the lessons and consultants from the Department of Art Education. The age of students involved in this research was 15 to 16 years; they were in the first grade of the high school at the time of the project. The school is situated in Prague 5 and it can be considered as an urban school. There are four year groups in this high school which focuses on the teaching of the English, French and German languages. The main aim of the successful study programme is to prepare the students for university study and similarly for the life inside and outside the school, with the focus on creative learning. At this high school level, students have two years of compulsory art lessons. Each art class consists of not more than 16 students and we had all together 32 students (2 groups) from this school participating in the Creative Connections project. The two groups were mostly described and labelled by their teachers as very different in their working and studying ethics and motivation, one group was very lively and difficult to handle and the other one as clever and reliable.

The first meeting with the students was done during the exhibition “My Place” at the Trafacka gallery in September 2012, where I had a chance to talk to the students about art and narrative for the first time. The idea of the ‘My Place’ exhibition was based on the permanent searching of the personal space, in which a person can find himself or herself and the space, where his or her thinking is rooted. This space can be understood as an actual place or as the state of mind. The ‘My Place’ project dealt with the idea of intertextuality, open texts and intervisuality in art. There was no text about the art works or artists included in the exhibition, therefore, the active participation and interaction in finding the meanings was needed from the audience and our students. The actual project, focused on fragments of narration, started in December 2012 and continued till May 2013.

Conceptual framework

Since there are stories where humans are, it was agreed with the art teacher that during this project, we would explore narration processes in the visual art deeper, with the focus on: the students’ main themes in their stories; how they communicate these themes and how these stories relate to identity issues. People think in terms of stories, they create stories and leave the stories behind them. It is interesting to realise that narrative and stories are all around us and that they are part of our everyday lives. By this, I do not mean people who read books every day or every night, but imagine that you meet someone after a very long time, a good friend perhaps, and you start chatting, and share your stories and adventures. You try to put, for example, a month into a story that has a head and a tail, into a narrative with the logical flow of the events. You are joining fragments into the story, similarly as Sherlock Holmes was joining all the little details in his deductions. As Roland Barthes said, narrative is transhistorical, transnational and transcultural (Barthes 1993, p.251). Narrative is truly everywhere.

The aim of the research project is to explore narrative, with the focus on the narration in comics, its logics, fragments, variations in particular stories, their dynamic and static characteristics. This different approach towards the stories in comics is based on the logics of film narration explored by Gilles Deleuze and theory of rhizome described by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. Critical analysis of the diverse approaches towards the structure of comics brought me to defining comics as a dynamic and changing medium, which needs for proper analysis both the structural and narrative study. Fragments are in this case understood as particular visual texts carrying the meaning and the part of the story. In fact, we can talk about the fragment as a time cutting or ‘a slice’ out of the narration. This kind of fragmentation is connected with making connections, with joining of fragments and overcoming gaps. We say that we construct the story. The reader fills in the gaps with his or her understanding of the story, understanding of the particular panels and pictures. Due to the popular visual culture, some of the fragments, sequences or logics of narration are already imported into the narrative structure of the reader, as well as the creator of the story. Students were expected to unconsciously use some of the imported fragments during their story creation. In this case, they were not working with the narrative as readers and creators with an innocent eye and untouched perception. They were facing the visual text with many competences for reading a picture already acquired and as Marie Fulková said:

This basic competence is usually acquired outside of the school; significantly the youngest generation acquires it through the influence of today’s visual culture” (2008: 186).

That is the reason, why I was focused during the research on the following questions:

1) How do students create the narrative?

2) Which fragments of narration are used by students in their own stories?

3) How do they understand and perceive these fragments and their role in the story?

4) What are the specifics of students’ visual narratives?

Detail of the scheme work

Before I describe the outcomes, I will shortly present how the particular lessons and lesson plans looked like.

The introductory stage: the stories in the pictures: The pilot study was the first meeting with the students in the Trafacka gallery. Throughout the exploring of the exhibition, students were asked to create stories or ideas for the stories from particular pictures or objects, which fascinated them the most. They were free to comment on the art works and leave the comments on the comment wall. Discussions in pairs and small groups were also done.

Sign and the meaning: The first two lessons were dedicated to getting deeper understanding of the signs and symbols, their possible meanings and usage in art from the point of denotation and connotation. Similarly, students were working with rarefied as well as saturated images (a totally blank space in comparison to four art works from our Creative Connection database – namely: S.Francová – Fotoblogy, A.Kotzmanová – Shopping is my hobby, M.Laakso – Coffee Break, J.Heikkilä – Mirja by the River). The students selected one of the mentioned art works and they tried to analyse it from the point of view of denotation and connotation. At the end, they were asked to create the story based on or inspired by the picture itself and to transform and re-interpret the picture by a new image.

Here and Now: Time plays an important role in the story. Through the series of quick figure sketches, students tried to explore their understanding of time, especially the past and the present. In this way, they created sketches as fragmented report from the lesson, bearing unconsciously in mind Deleuze’s idea about the present and the past:

Since the past is constituted not after the present that it was but at the same time, time has split itself into two at each moment as present and past (Deleuze 2011: 79).

In one case, a student created a time collage of sketches, drawing fragments like feet, portraits, hands, semi-figures on one piece of paper. The past and the present were mixed in this way together, leaving the reader a space for his or her own understanding of what had happened during that art lesson.

Fragments of narration in comics: Comics are a fragmented narrative, an assemblage of fragments joined together. This lesson served as an introduction to the narrative in comics and possible fragments which can be used for the creation of comics’ narrative. Together with students we discussed the narratives brought as examples. Students tried to define the main characteristic features of the narratives and then according to a short script of one page from an original comics’ story, they worked and created a page from a comic based on the script provided. From this activity the students had a chance to compare their way of breaking the story into meaningful fragments and understanding of the same text.

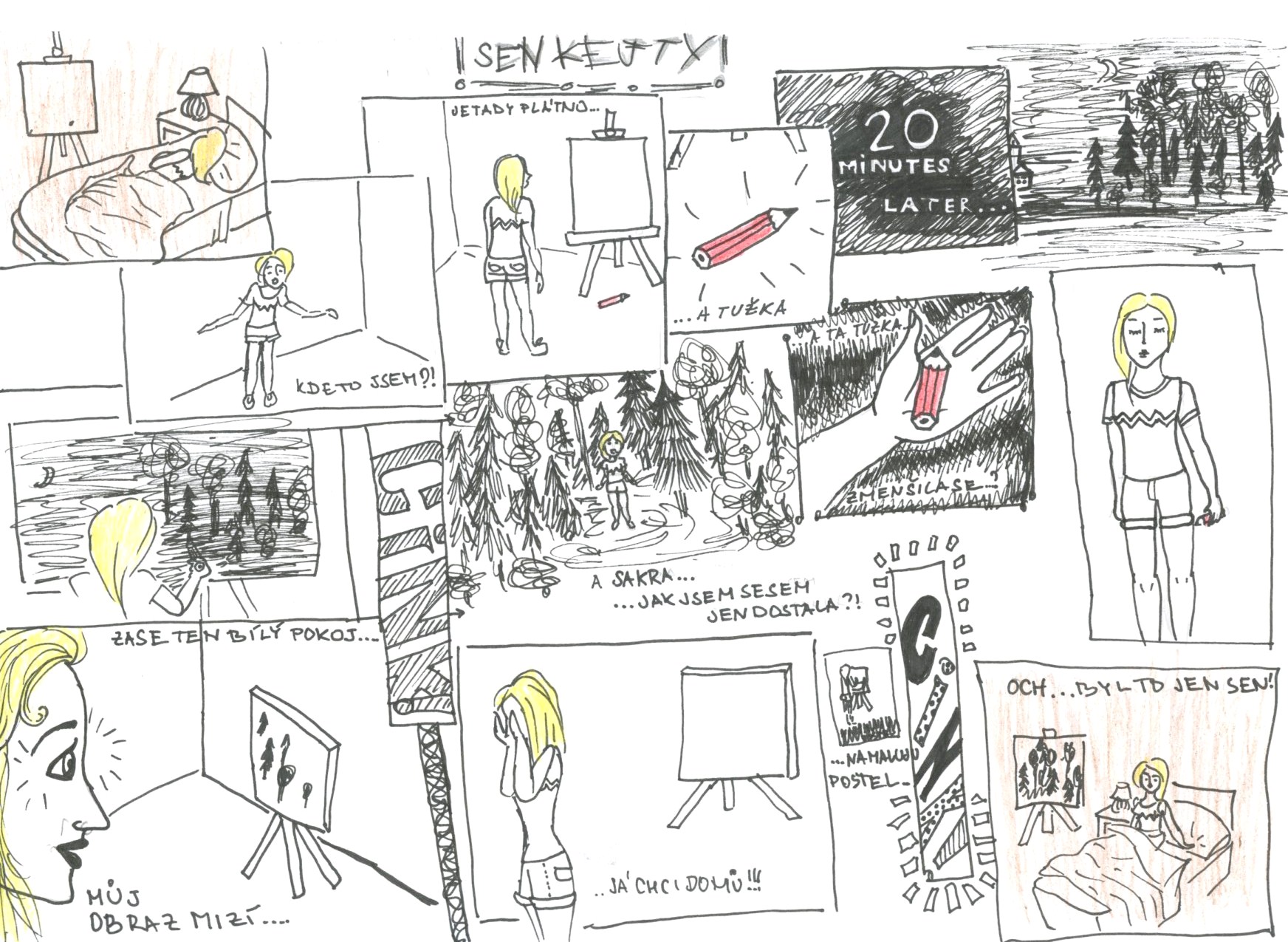

Dream images, dream sequences: Another series of lessons focused on one of the possible main themes/images in comics which not only dealt with the creative way of how to present the dream image in the narrative, but also with creative writing, preparing students’ own ‘dream story’ and working with the montage of images as such. Those were the stories which not only focused on dreaming and day-dreaming but also on hallucinations and visions caused by illness or disease. On the one hand, students preferred to explore the narrative with humour and irony, on the other hand, they wanted to explore the themes which are not so humorous and deserve our attention (e.g. identity problems, drugs, anorexia and bulimia). From the point of view of storytelling and constructing of the narrative, students encountered problems with fragments’ order and place in the whole narrative, logics of narration and selecting the right piece of the story, which would be readable for possible readers and audience and not just for the author of the story.

Animation: montage and fragments: The final series of lessons was focused on using all the narrative knowledge students acquired or had before. Students were asked to prepare in small groups a script for the animation narrative; on any theme they were interested in. This stage was followed by the preparation stage. Some of the students decided to play in their own animation as characters, some created characters from paper, clay or other material provided. Animation was created through stop-motion animation. Then the final editing was carried out digitally on PCs. Themes, selected by students, mostly dealt with love issues, identity, minority problems or irony. The students were not afraid to use technical ideas they had learned during the previous lessons and those which they already knew, for example from films, music videos and advertisements (e.g. zoom-in or flash forward fragment).

Changes made as a consequence

There was one theme I did not explore with students as I wanted, according to the first version of the project plan. The theme was exploring problems of memory. However, students presented these in their own writing and stories, without me preparing a lesson for this particular theme. They used a collage of their memories in their stories or employed flashbacks quite often. For instance here is an excerpt from a student’s narrative:

Kail was sitting in his room, which used to be his sanctuary, a place, where he was able to do everything he wanted. The walls, which used to be so colourful, were now naked with visible stains left behind by his posters. His room was as empty and depressing as the whole flat: the flat, where he grew up; the flat, where he spent good and bad times with his parents and a little sister. He stood up and went to another room, which used to belong to his sister. There was the same emptiness. However, he did not see that. He was not looking into the present, but into the past. He saw two teddy-bears sitting on the white bed and his little sister leaning to them, with her blond hair hiding her face. She was asking them to take care of her room while she was at school that day.

Another change was needed straight after the first lesson. We found out that students needed more time to understand the signs and symbols theories better. Therefore, another lesson was dedicated to signs, denotation, connotation and symbols was prepared for them, where the students had a chance to prepare their own reactions (mostly in the form of photographs) on the art works that we were working with during the previous lesson.

The project showed us that together with students, we had to spend more time on timing and ordering of the particular images in the comics narrative structure, because in some cases during narrative construction unexpected problems caused misunderstanding of the stories such as: ordering and reading the images from right to left, boustrophedon ordering of the images or reading and ordering the images from the bottom to the upper part of the page.

Lessons learned and findings

Creating the story and comic narrative is a process quite different for every author. When it came to the creation of the story, it was very individual for every student. At the beginning, they liked to work in small groups and pairs, especially because they shared and compared their ideas. However, just one pair of students decided to cooperate and create the comics narrative together. All the others worked individually. The reason was simple. They like to share and compare the ideas, but the final story should be theirs, as one student explained.

We created the main character together in a small group. Firstly, we had some crazy ideas, but then we agreed that the character will be an attractive blond and she will be a painter. However, there will be something strange about her – everything she paints turns into reality. Then we had a problem and we could not agree on anything further. Somebody wanted her to be on a deserted island, someone else in the empty room. So we decided to work on the story from this point individually.

During an interview with a Finnish comic author, Mari Ahokoivu, we talked a lot about the narrative of comics and their connections to the author’s life. She said her stories were at least semi-autobiographical and she argued that every author puts something from her or his life into their stories. A similar thing happened with our students. When we discussed the stories they created, most of them were talking about their wishes, needs and dreams, and not of those of their characters. They also created characters which were as either too attractive and beautiful or too strange and disgusting, showing in some ways how the students would or would not like to be perceived by the others. Constructing a story was more difficult for students than I imagined at the beginning of the project. However, we have learned a lot together with students not only about the imported fragments and narrative structures they were using naturally (e.g. zoom in, flashbacks, flash forward) but also about the problematic issues when creating and constructing the comics story. The ordering and logical flow of the images and panels was sometimes a problem for them a further obstacle was the tightly bound relationship between comics and illustration. On the other hand, comic narrative gave students a more space to explain themselves clearly and to write and draw a story which was partly about themselves and not only about their characters.

References

Barthes, R. (1993), The Semiotic Challenge. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Deleuze, G. – Guattari, F. (2010), Tisíc plošin. Praha: Herrmann & synové.

Deleuze, G. (2011), Cinema I. Londýn: Continuum.

Deleuze, G. (2011), Cinema II. Londýn: Continuum.

Duncum, P. (2009), Towards a Playful Pedagogy: Popular Culture and the Pleasures of Transgression, Studies in Art Education, 50 Spring, pp. 232-244

Eco, U. (1989), The Open Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Eco, U. (2009), Meze interpretace. Praha: Karolinum.

Fulková, M. (2008), Diskurs umění a vzdělávání (Discourse of Art and Education), Praha: Herrmann & synové.

Gombrich, E.H. (1985), Umění a iluze. Praha: Odeon.

Goodman, N. (2007), Jazyky umění, nástin teorie symbolů. Praha: Academia.

Groensteen, T. (2005), Stavba komiksu. Brno: Host.

Hendl, J. (2005), Kvalitativní výzkum. Praha: Portál.

Howells, R. (2003), Visual Culture. Cambridge: Polity Blackwell Publishers.

Penn, G. (2006), Semiotic Analysis of Still Images, in Bauer, M. – Gaskell, G. (ed.), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound, London: Sage, pp. 227-245

Seppänen, J. (2006), The Power of the Gaze. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Strauss, A. - Corbin, J. (1999), Základy kvalitativního výzkumu (Postupy a techniky metody za-kotvené teorie), Brno, Boskovice: Sdružení Podané ruce a Nakladatelství Albert.

Varto, J. (2008), Art and Craft of Beauty. Jyväskylä: Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy.

Wilson, B. (2005), More Lessons from the Superheroes of J.C. Holz: The Visual culture of Childhood and the Third Pedagogical Site, Art Education, 58 Nov, pp. 18-34

Wilson, B. (1997), The Quiet Revolution (Changing the Face of Art Education). Los Angeles: Getty Education Institute for the Arts.