The Role of the Connected Gallery

Annamari Manninen and Mirja Hiltunen

Finnish team

Contemporary art provides an opportunity to reflect on contemporary society and the issues relevant to ourselves, and the world around us. -- .Contemporary art is part of a cultural dialogue that concerns larger contextual frameworks such as personal and cultural identity, family, community, and nationality (New York University. 2014. Definitions).

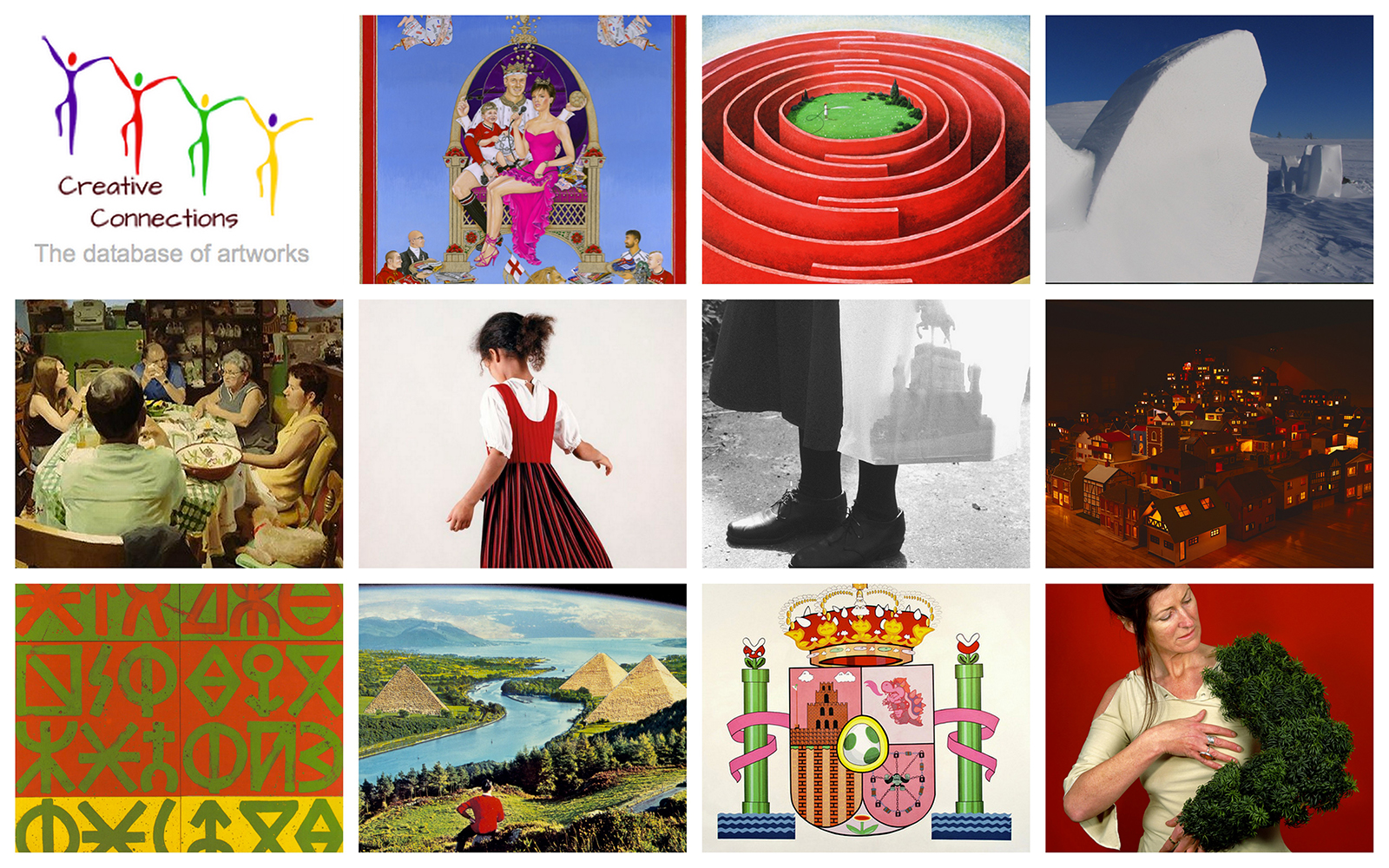

The Creative Connections project’s aim was to explore and develop ways of increasing understanding of European identity among children and young people by connecting art and education. The Connected Gallery works as a model for analysis of contemporary art, which allows for collaborative activities and dialogue in a multicultural environment.

Students from the six partner countries created artworks based on the Connected Gallery and communicated with one another via blogs on the website. The Connected Gallery offers various approaches to art so that teachers can deal with the themes of personal, local and national identity and ‘European connectedness’ from different perspectives.

Art makes us see ourselves and our relation to the world we live in. Art education helps to observe differences in human cultures and promotes an ethical attitude towards the unfamiliar. In order to understand other individuals and cultures, we need skills to interpret the art they make (Räsänen. 2012:1, see also Räsänen. 2008).

The Selection of the Artworks and the Structure of the Gallery

The Creative Connections Connected Gallery was created in the beginning of the project to serve as inspiration and material in the school projects. The foundation of the gallery was a selection of artworks collected in the previous research project Images and Identity (2008-2009). Creative Connections challenged us to find artworks from the six participating countries and create categories to organize the gallery. In the Images and Identity project the teachers tended to use artworks only from their own countries, so the artworks for this new project were grouped differently to encourage exploration of examples from all countries.

The Connected Gallery was intended also to be used for exploring different approaches to learning which is required by the different roles of art. The database was divided into five categories (A-E) developed by Hiltunen (2009) and based on what Lacy (1995) describes as the different roles of art. The aim was to cover the whole range of contemporary art from the different materials and techniques to the different approaches and ways of working which artists use today. Besides the traditional self-expression and visual reporting, the idea was to present also community art, site specific art and environmental art based on Coutts & Jokela (2008), Kester (2004), Kwon (2002), Neperud (1995) and Sederholm (2000) by defining these new art forms and approaches.

With the given guidelines, the national teams each proposed around 20 artworks for the gallery. The Finnish team coordinated the creation of the gallery and made the final selection from almost 120 pieces of works to 74. The aim was to have a balanced selection of topics, different media and nationalities presented. After the selection, the artists were contacted in order to ask their permission to use their work; some refused so the final version of the gallery currently has 64 artworks. The topics for the categories also developed their final form in the selection process.

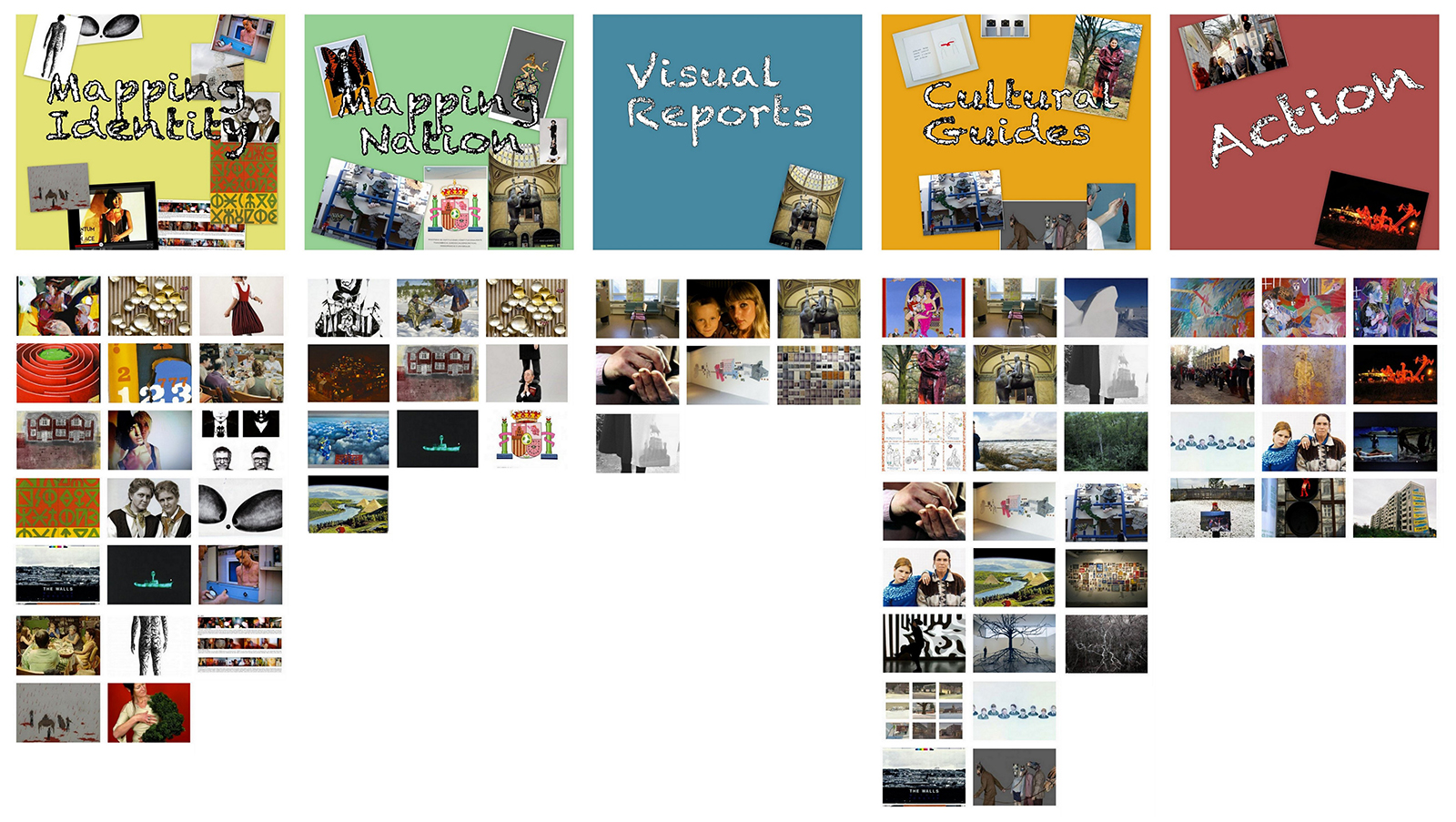

The Connected Gallery categories:

- Category A: Mapping Identity reflects upon the students’ personal growth by identifying different aspects of identity;

- Category B: Mapping Nation examines how identity is influenced by the surrounding culture;

- Category C: Visual Reports facilitates students to act as reporters who pay attention to the cultural environment;

- Category D: Cultural Guides serves as a guide for examining, seeing and presenting things in different ways;

- Category E: Action! presents activism as the guiding factor for encouraging students to participate and act in their own locality.

The use of the Connected Gallery in the School Projects

The research phase of the Creative Connections project in schools saw the Connected Gallery used in many ways to explore the themes of European citizenship and connectedness. Artwork examples were used by teachers to discuss ideas and by pupils who were making their images. The following review on the use of the gallery is based on the information provided by all the 25 case studies from the school projects. The artworks have been used as introduction to the theme and mainly as tools to start discussion. The selection of artworks was left to the teachers who chose works of art suitable for their pupils in terms of age and theme. Pupils sometimes had a say in the process of selecting artworks and teachers used images or artists that pupils found particularly interesting and wanted to explore more closely.

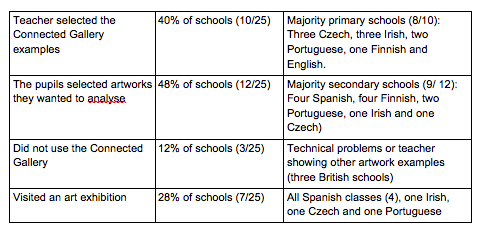

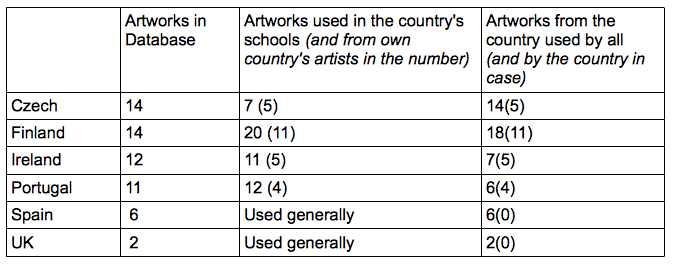

Table 1: The use of the Connected Gallery and selector of the explored artworks

The review of use of the Connected Gallery shows that with the younger pupils the teachers more often selected the images to be explored and discussed. There are differences in approach between countries. For example in Irish schools it was usually just one artwork selected to work with in the class. By contrast in the Spanish schools the pupils usually viewed the whole gallery and could choose the artworks interesting and suitable for their project. The three schools that did not use the Connected Gallery either due to the lack of projector to use in class, or because the teacher chose to use other materials, were all from UK but exploring contemporary art and contemporary art techniques were also part of these schools' projects.

Seven school classes also visited a contemporary art exhibition as addition to the Connected Gallery examples. In Ireland pupils of one participating class were lucky to be able to see works of Alice Maher in a museum. In Portugal, one class visited a local exhibition of artist Manuel Lima and examples of his works were added to the Connected Gallery.

The pupils analysed the artworks through discussion, questioning and writing, but also by making their own versions and imitations of the images. Using the same artworks in different countries and schools has raised the question of how the same image can be seen and understood from different perspectives and cultural backgrounds. The blogging environment enabled sharing of these different interpretations.

Example 1: The Artworks were visually analysed by making new versions by drawing, painting and staging photographs. Image: Alena Kotzmannová's work: Shopping is my hobby and the reinterpretation of Czech pupils.

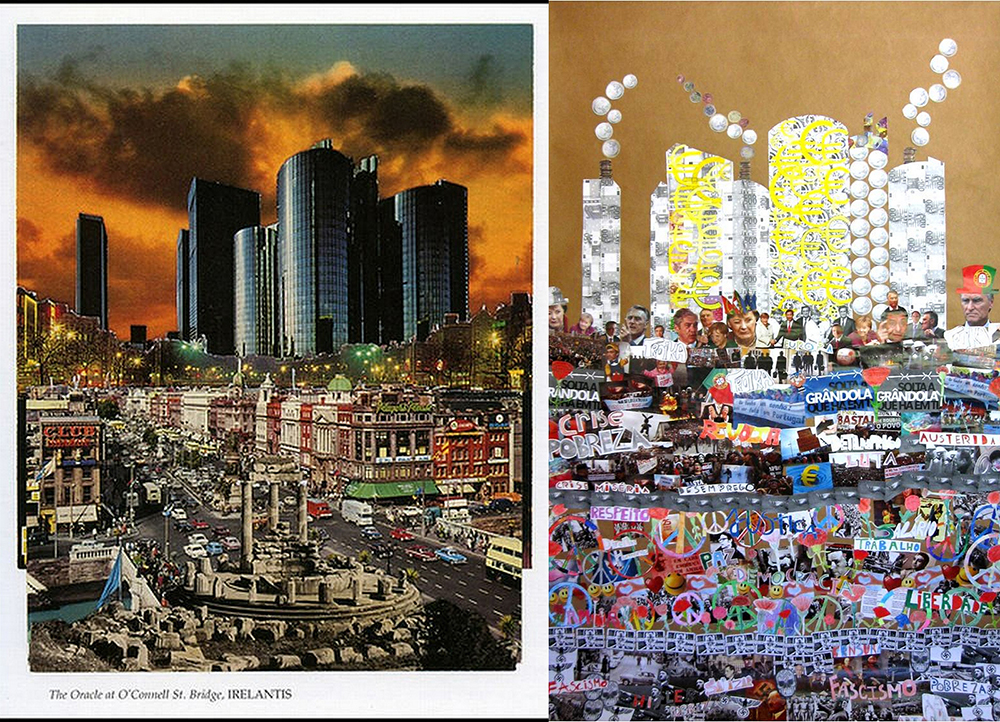

Example 2 & 3: The topics, techniques and visual structure of the artworks served as an inspiration for the pupils' art projects. One Portuguese class analysed the work of Sean Hillen and made their own vision of a cityscape with the layers of past, present and future, by imitating the composition of the work and using the same collage technique. Image: Sean Hillen: The Oracle in the O’Connell Street Bridge, Irelantis and children's work: Money rules in Europe.

The works of Alice Maher, who explores the relation to the nature, inspired many Irish classes to work with natural materials and to define their relation to surrounding environment and nature. Alice Maher's work 'Limb' and Irish pupil's experimental print work with a leaf.

For the older students, artworks and the categories have served as an example of the different forms and roles of contemporary art. Connected Gallery was used in dialogue with their own work process. Many created their own art projects according to these aims and methods presented in the artwork examples in the gallery.

Example 4: The Artworks and categories showed what issues art can address and how those issues can be visually approached. One of the Spanish classes made art projects in small groups with topics chosen by the pupils themselves. They used the Connected Gallery in dialogue with their process to get ideas for their own work. Some artworks were used to reflect their topic, some to inspiration for aesthetic style and others to get idea for the format and technique. Image: Murals by one of the groups with the theme “Art of Sport” and one reference artwork Petri Hytönen's painting “Finland – Sweden”.

Teachers used the Connected Gallery to:

- Generate discussion / promote conversation (32%)

- Make re-interpretations of artworks/ create responses to an artwork (28%)

- As examples and inspiration (24%)

- Demonstrate roles of art, notions of stereotypes, concepts of how to present something(16%)

- Analyse and explore visually and literally artworks (16%)

- Introduce the project or theme (12%)

- Create dialogue with other images and own art making (8%)

- Increase awareness (art & social issues) (8%)

Many schools used the Connected Gallery widely and in versatile ways. The mentions in the case studies are the planned with intentional use of the Connected Gallery. In the reality the gallery might have worked as introduction and created discussions in many more cases than in the ones actually mentioned in the case studies. The activities are also partly overlapping since it is a question of what terms the teachers used to describe the activity. For these reasons, the percentages presented above indicate more the teachers’ emphasis on the use of the gallery and what role the gallery images they found important in the project and thus reported in their case study. For example few teachers intentionally used the gallery to increase the awareness of contemporary art in their class. However, some teachers reported the same as a result of the project, when they used the artworks to generate discussion and introduction to the theme.

The Popular Artworks

The facts of which artworks were most used and by whom, are important in developing the gallery for educational use. The use of artworks from different countries and by the countries is described in the following table. The use of artworks is similar to the amount of artworks presented from that country in the gallery. This is seen also from the fact that each country has used artworks half of which are from their own artists and the rest from the other five countries. The fact that there were only two UK artworks in the gallery, may have affected the UK schools’ attitude to using it as a resource.

The results include not only the specific use of artworks but also the general use of the gallery, therefore they do not provide an indicative picture of usage.

Table 2: Use of Artworks by Countries (mentions in case studies)

In the case studies there are also some artworks which appeared generally more popular. Particular artworks were used by many of our participants and explored and interpreted in works in several countries. Finnish artist Markku Laakso's painting “Coffee Break” picturing Elvis on campfire with Sami girl serving him coffee in snowy forest got the most attention (from five schools, three of these were Finnish). Czech painter Eduard Ovcacék´s “Signs” with language and letter related subject was explored in four schools (two Finnish, one Czech and one Portuguese). As well as Jaakko Heikkilä's photograph “Mirja by the River”. Michael de Brito's paintings of family dinners were selected by teachers in three schools (in Finland, Portugal and Czech) commonly with younger pupils for themes of family, customs and community.

There is also a difference between the artworks mentioned in the case studies and the artworks referred to in the works of pupils in the Quad Blogs. There are clear visual references to some mentioned artworks found in pupils' works, but not for all (for example to Markku Laakso's Coffee break). This indicates that some artworks were especially useful in starting conversation and others inspired visual representations, and some both. Some artworks seemed to appeal especially in their own country. For example, Alice Maher's work was used and analysed in three Irish schools, but not mentioned being used in the schools of other countries.

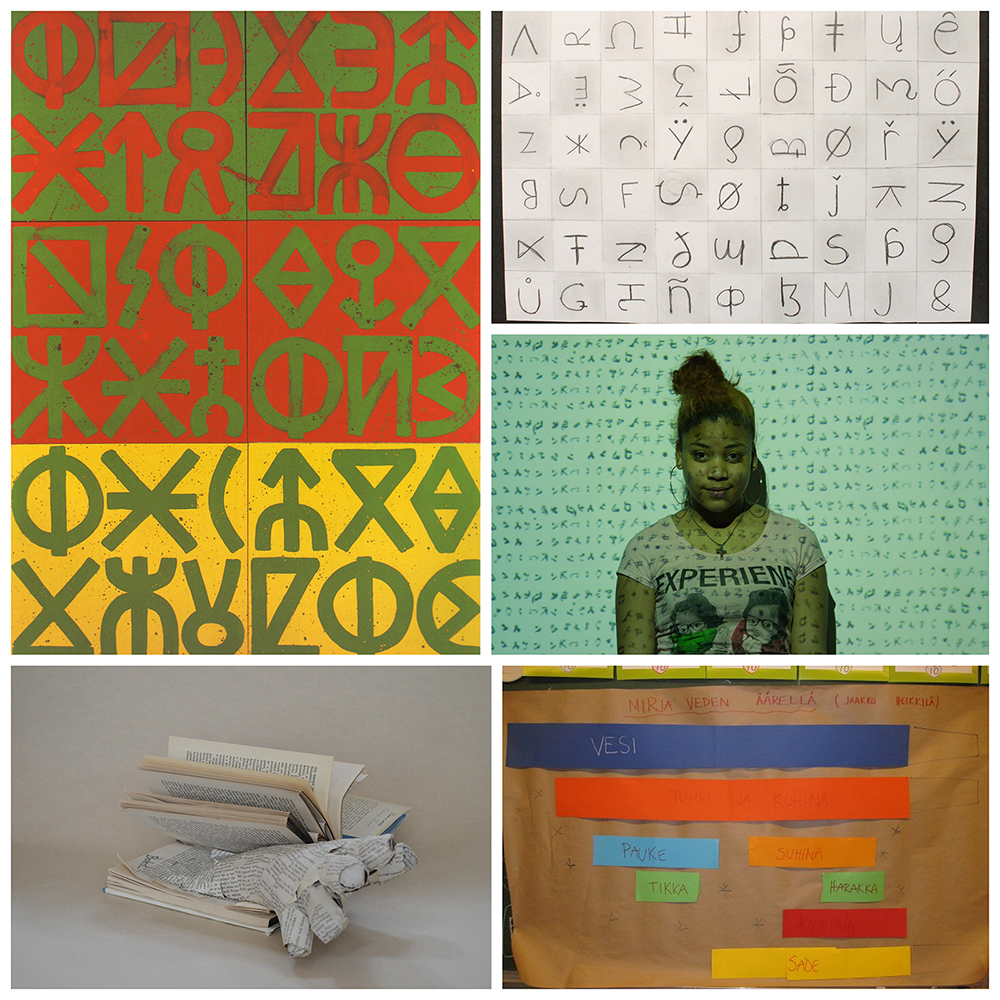

Image: Examples of the various use of Eduard Ovcacék's painting:

The original work “Signs”,

• a Finnish pupils version of the painting in drawing,

• as visual inspiration for exploring signs in Spanish pupils group work,

• as inspiration through language and writing for the theme “Book as me” in Czech school project,

• as interpretation to a sound work – a Finnish class creating a soundscape for the painting.

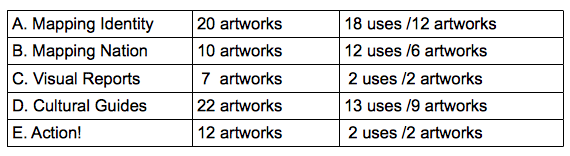

The Use of the Categories: the different approaches to art in school projects

We examined the ways in which the artworks were used according to the different categories created for the Connected Gallery. Teachers could choose to work according to a theme or select artwork examples from here and there when using the Gallery.

Table 3: Use of artworks by gallery categories (mentions in case studies)

When looking at the use of artworks, the categories A, B and D have the most frequent use and these categories also contained the largest amount of artworks. Notably, these three categories are linked through the themes of exploring identity and cultural meanings. The topics of personal, local, national and European identity were present in most of the schools projects.

The artworks from categories of visual reporting and the activist art have only few mentions in the case studies. Still the approaches to art making, introduced in these categories, have been present in the school projects. Many of the pupils’ works are reports of their life and surroundings. For example the drawings of pupils from Portuguese Vila Praia de Âncora and Finnish Utsjoki, document the everyday life and traditions in their communities. Also many art projects have been taken out of the classrooms to make statements and pupils opinions heard. The idea of using art to make a change and impact is part of the activist art. One of the Spanish schools made especially strong project in creating several installations and taking over their environment to express their feelings and opinions on current economic situation that is reflected in their surroundings concretely in a new school building left unfinished.

Image: Escola Serralavella: “Money in the sewer” comments on the economic crisis and politicians misusing money; Pedestrian crossing towards the unfinished school which includes the consequences of cutbacks in education, health, work, school, justice, etc. And “We want the new School!” work was made with the participation of all children in the school. The names of the pupils glued to the fence that bars access to construction site of the new school building. Pupils hope to enter the school and they are demanding that the building is finished to stop having class at the barracks.

The Connected Gallery as a Blog

The Connected Gallery on the project website was also in a form of blog, which enabled leaving comments below the artworks. This feature was not instructed nor especially planned how it would be used in the project. Originally there was an idea of commenting on artworks with images. Unfortunately despite the effort it turned out technically impossible to include images into the blog comments.

Still during the project the artworks got 38 comments in the gallery blog. The Connected Gallery was different from the quad blogs used by the schools, since all the participating pupils, students, teachers and researchers had access to it. The comment left to an artwork in the blog was visible to all who were looking at that artwork.

The comments consisted of a few long comments with the pupils’ views and analysis of the work posted by researchers and teachers and the rest of the comments are made up of pupils’ short spontaneous comments on the works (mainly by pupils from the schools of Larkin, Bevin and Utsjoki). The comments vary from “cool” to “scary”. Some of the comments are addressing the artist directly, even asking questions about the artwork. This opens up new ideas and possibilities to future forms of the Connected Gallery blog as part of an art education project.

The Impacts of Using Contemporary Art/Connected Gallery

The case studies from the schools report also the impact of using the Connected Gallery images and contemporary art in general in the schools. Teachers and researchers found that it changed the pupils’ understanding of art, developed visual literacy and awareness of art as a political tool. The artworks also made pupils think, understand concepts and reflect their identity and social issues. The Connected Gallery worked as a space for dialogue and expression, to talk about emotions, opinions and pupils themselves. The work around contemporary art gave freedom to an open ended process.

The experience encouraged teachers to show and discuss images and artworks more with the class since the image analysis was found as an educational tool. They were surprised to learn new things about their pupils, while the pupils’ responses to contemporary art were different from looking at examples from art history.

As a conclusion we can say that the numbers of artworks used and their visual impact that can be distinctly seen in the pupils’ work and shows that the Connected Gallery has had a meaningful role on the Creative Connections project. The case studies give only one perspective to the use of Connected Gallery; especially the statistics on popularity of the certain artworks. Further studies on the data are needed to understand the role the Connected Gallery in the project. A glance at the postings in Connected Gallery blog show already a parallel yet different view in the use of gallery and the pupils thoughts about the artworks. The analysis of the lesson plans and quad blog postings are planned to be part of the ongoing research process and will be taken into account in the final research results. The Creative Connections Connected Gallery is an example of how contemporary art can be used to approach contemporary issues and connect art with multicultural and civic education.

References

Couts, Glen & Jokela, Timo (eds) (2008): Art, Community and Environment: Educational perspectives. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Hiltunen, M. (2009). Yhteisöllinen taidekasvatus. Performatiivisesti pohjoisen sosiokulttuurisissa ympäristöissä. / Community-Based Art Education. Through performativity in Northern Sociocultural Environments. Acta Universitatis Lapponiensis 160. Lapland University Press / Lapin yliopistokustannus

Images and Identity. 2008-2009. Mason, Rachel (Project director). www.image-identity.eu.

Kester, Grant H. (2004): Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkely and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Kwon, Miwon (2002): One place after another. Site specific art and locational identity. London: The Mit Press.

Lacy, Suzanne. (1995). Mapping the terrain: new genre public art. Bay Press: Indiana University.

Neperud, Ronald, W. (Ed.) 1995: Context, content and community in art education: beyond postmodernism. New York: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

New York University. 2014. Definitions. Department of Art and Arts Professions. Steinhardt school of Culture, Education, and Human Development. Available on website: http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/art/education/definitions

Räsänen, Marjo. (2012.) Cultural identity and visual multiliteracy. Article in magazine Synnyt/ Origins 2/2012. available online: https://wiki.aalto.fi/download/attachments/72901592/Rasanen.pdf?version=1

Räsänen, Marjo. (2008). Kuvakulttuurit ja integroiva taideopetus (Visual cultures and integrative art teaching). Helsinki: University of Art and Design, publication B 90.

Sederholm, Helena 2000: Tämäkö taidetta? ( Is This Art?) Porvoo: WSOY